There are many who are concerned with the amount of pesticides farmers apply to the crops we eat. Not only are many concerned with the harm pesticide residues cause when they eat this food, they are also concerned with the effect these pesticides have on the environment. Perhaps you are concerned as well.

According to the EPA, “World pesticide expenditures totaled more than $35.8 billion in 2006 and more than $39.4 billion in 2007. U.S. pesticide expenditures totaled $11.8 billion in 2006 and $12.5 billion in 2007.” This is from the EPA’s Pesticides Industry Sales and Usage – 2006 and 2007 Market Estimates report.

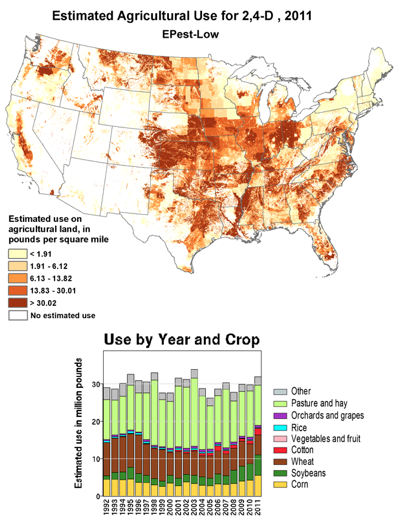

The USGS (US Geological Survey) has a web page, The Pesticide National Synthesis Project, where you can find maps showing estimated annual usage for more than 460 pesticides; pesticides like Acetochlor, Clothianidin , Dichloropropene, and many more. This is what one of these maps looks like.

This map shows the estimated usage in pounds per square mile of 2,4-D, a chemical used in Agent Orange. The map also show the different crops it is used on. So you can look up a pesticide and see if it is used extensively where you live.

This map shows the estimated usage in pounds per square mile of 2,4-D, a chemical used in Agent Orange. The map also show the different crops it is used on. So you can look up a pesticide and see if it is used extensively where you live.

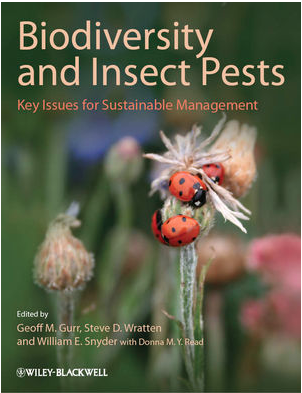

In Biodiversity and Insect Pests, edited by Geoff M. Gurr, Steve D. Wratten, William E. Snyder, with Donny M. Y. Read, the writers make the case that incorporating biodiversity into farms can reduce and even eliminate the need for pesticides. Agriculture, which now accounts for 40% of the land area on our planet, has greatly diminished the diversity of plants, animals, insects and organisms. As a result, agriculture is responsible for greatly reducing the number of beneficial insects which are needed to keep the pest insects under control. And with agriculture practiced on an industrial scale, ever increasing amounts of pesticides are used to keep pest insects under control, resulting in even greater losses to biodiversity.

The book explores the ways biodiversity can reduce pests, and be a source of genes for better crops and compounds for botanical insecticides.

Biodiversity and Insect Pests is a technical book, detailing numerous experiments from around the world. One example I particularly liked was the use of flowering plants, like alyssum, to protect lettuce fields. The way this works is that many predatory insects which kill pest insects do not actually eat the pests. Instead they lay their eggs in the pest insects, and when the eggs hatch, the larvae devour the pest insects. But when you have, for example, a field of lettuce which covers hundreds or thousands of acres, there is nothing for the predatory insects to eat, so they don’t venture far into the lettuce to lay their eggs on the pests.

However, if farmers plant rows of alyssum along with the lettuce, the predatory insects thrive off the pollen on the alyssum, and will spread through the field, laying their eggs in the pest insects, and keeping them under control. Planting a variety of flowering plants in these strips is also helpful, as different predatory insects feed on different flowers.

At the same time, the writers point out the importance on relying on more than one predatory insect. They stress the need to have strips of undisturbed rows or land nearby for other predatory creatures, like spiders. Many predatory bugs live in burrows in the ground, and so are totally absent in fields that are plowed and tilled. The way having multiple predators helps, is that some pest insects will drop to the ground or flee when they are attacked by predatory insects. By having healthy populations of ground level predators, the pest insects can be mopped up by these ground level predators.

The writers point out that the financial benefits of biodiversity are usually not counted in economic studies. And yet, they point out that ecosystems can provide significan economic benefits. They state that “the value of coffee borer control by birds in Jamaica has been estimated to be US$310 per hectare,” and that in the cotton fields ofTexas, the value of insect eating bats is estimated to be US$5 to US$70 per hectare. In 2006, researches Losey and Vaughan estimated that insects provide services, such as pest control, worth US$4.5 billion.

For example, a key pest of vines in New Zealand is a leafroller caterpillar, Epiphyas postvittana (Walker), which can be managed by planting buckwheat or other nectar plants between vine rows to improve the ecological fitness of its key natural enemy, the parasitoid wasp Dolichogenidea tasmanica (Cameron) at a cost of NZ$2 per ha. There is no loss of productive land and annual variable costs of NZ$250 per ha can be saved (Scarratt, 2005) indicating a cost–benefit ratio of 125:1.

Biodiversity and Insect Pests is a fascinating book with numerous examples of how to incorporate biodiversity not only into farms, but also into urban gardens, so that you don’t need to use synthetic pesticides to control problem pests. At the same time it is a very technical book written for researchers. Hopefully, the writers will come out with a companion book for the lay person, with easy to read examples of how to incorporate biodiversity into their gardens and vegetable plots to eliminate the need for pesticides.

The chapters in the book are:

- Chapter 1 Biodiversity and insect pests

- Chapter 2 The ecology of biodiversity-biocontrol relationships

- Chapter 3 The role of the generalist predators in terrestrial good webs: lessons for agricultural pest management

- Chapter 4 Ecological economics of biodiversity use for pest management

- Chapter 5 Soil fertility, biodiversity and pest management

- Chapter 6 Plant diversity as a resource for natural products for insect pest management

- Chapter 7 The ecology and utility of local and landscape scale effects in pest management

- Chapter 8 Scale effects in biodiversity and biological control: methods and statistical analysis

- Chapter 9 Pick and mix: selecting flowering plants to meet the requirements of target biological control insects

- Chapter 10 The molecular revolution: using polymerase chain reaction based methods to explore the role of predators in terrestrial food webs

- Chapter 11 Employing chemical ecology to understand and exploit biodiversity for pest management

- Chapter 12 Using decision theory and sociological tools to facilitate adoption of biodiversity based management strategies

- Chapter 13 Ecological engineering strategies to manage insects pests in rice

- Chapter 14 China’s ‘Green Plant Protection’ initiative: coordinated promotion of biodiversity-related technologies

- Chapter 15 Diversity and defense: plant-herbivore interactions at multiple scales and trophic levels

- Chapter 16 ‘Push–Pull’ revisited: the process of successful deployment of a chemical ecology based pest management tool

- Chapter 17 Using native plant species to diversify agriculture

- Chapter 18 Using biodiversity for pest suppression in urban landscapes

- Chapter 19 Cover crops and related methods for enhancing agricultural biodiversity and conservation biocontrol: successful case studies

- Chapter 20 Conclusion: biodiversity as an asset rather than a burden