I’ve never seen two old love birds like Billy and Imelda. They’re not exclusive, mind you. Billy continues to cavort with plenty of other hens, but Imelda has a special place in his heart. They spend a lot of time together, and this afternoon when I saw Billy standing in the doorway of one of the doghouses, I went to investigate what he was doing.

He was watching out for Imelda, who was in the doghouse to lay an egg. He hovered around her for half an hour or so.

He was right next to her when she laid this egg.

And afterwards, he followed her around. The two make a touching pair. He is five years old and she is four. For chickens, they are well into middle age.

There is more going on in their tiny brains then we realize.

The Beauty of Growing Produce

Growing vegetables and fruits is like living in an art museum. Every time I step out into the vegetable patches to weed, thin, and pick vegetables, there is more beauty than I can possibly absorb.

There are many artists who are known for the flowers they draw. Where are the artists painting growing salad greens or blooming herbs?

Teaching Them to Feed

Chicks will grow up without a mother hen to teach them how to feed. But when they do have one, they follow her around everywhere, watching what she is doing, what she eating, how she is digging it up, and finding out what she finds especially delicious.

[wpvideo QbqTWTwC]

Dandelions

Biking home from the post office this afternoon, I had to stop and take some photos of a field full of dandelions.

Look closely at each dandelion, and you quickly realize that it would take hours and hours for a person to make one flower. Each of the hundreds of seeds on a single flower has a fine stem. At the end of these stems are 30 to 40 fine threads attached which form the parachute the seeds use to fly away.

How long would it take to make one parachute and attach it to one seed? How long would it take to make the hundreds required for one flower? How about making the tens of thousands to decorate a single field?

And yet, no one has to lift a finger to make a field of dandelions so beautiful you just have to stop to take a look.

The Continuing Evolution of Genes

Carl Zimmer writes today in the New York Times in The Continuing Evolution of Genes that scientists used to believe that the some 20,000 genes we all have, came from our parents, which came from their parents, and on backwards to the very first forms of life. And that the genes all organisms have, can be traced back to these original genes.

The thinking was that at first there were just a few genes, and at times when they duplicated, making two copies of the same genes, which over time evolved into different genes, hence the increasing number and complexity of genes we now find.

With new genes evolving from earlier ones, it would be possible to compare the genes and see which genes came from which genes.

But when scientists gained the ability to read DNA sequences, they discovered that though most genes were duplicated versions of earlier ones, there were also a number of genes which were unique to a species. They called these orphan genes de novo genes. Unlike most genes which have been passed down through the generations for billions of years, de novo genes came into being much later.

Carl Zimmer’s article explains how these orphan genes came into existence, and the role they play in evolution. The article is worth a read. It also has a podcast with a segment describing the origin of genes.

One thing I am trying to find is a scientist who is researching how instinct is encoded in DNA. The first time one of my hens hatched and raised a clutch of chicks, it made me wonder how she knew how to that. She was a hatchery chick and raised without a mother. So how did she know that if she sat on an egg for 21 days that they would hatch. And all of the hens I’ve observed, use the same calls for danger, here’s good food, be quiet, etc. And all the chicks know from birth what these calls mean.

So how is all that complex behavior inscribed on DNA? I’ve come up with many scientists researching genetic behavior and trying to determine what behavior is genetic and what is learned. And scientists knocking out genes in organisms like flies to see how those genes affect fly behavior and the like. But I’ve yet to find the scientists looking at the GATC letters of specific DNA to tease out how complex behavior is carried by DNA from generation to generation. I’m sure it is extremely complicated, but hopefully there is a scientist out there who is studying this and can explain how nature does this amazing feat.

They Are All Unique

How do you tell them apart? When they are this young, like these eight chicks hatched yesterday, there is one that pops out because it is a different color. The rest look the same, but if you look closely, you’ll see little differences in the coloring, the feet, the faces, and the personalities. Some stay close to their mothers. Others are more adventurous. Some are quiet, others loud.

As they grow up, their differences shine. You would never mistake these two hens. Their coloring is very different, but so are their combs and wattles, their faces, and their beaks. Compare the combs on these two hens. One has floppy, rounded teeth on her comb. The other upright, pointed ones. There is an infinite variety of combs. Some flop left. Some flop right. Some both ways. Many are straight. Looking at their combs is one of the easiest ways to tell chickens apart.

Their personalities also stand out. Stay in one place very long, and Billy and his consorts are sure to come by. You might say some roosters develop an entourage. To keep an entourage, they have to work at it. Hens won’t stick around if they aren’t being treated right.

Of course, if you pack in chickens cheek to jowl, and only have hens, the dynamics change. In the wild, chickens never end up cheek to jowl. They spend as much time alone as they do with the rest of the flock. So it makes me think that chickens raised in the artificially super-packed quarters most are, must be under continuous stress, not know how to deal with having so many others around them all the time, and never having any time alone.

On a place like a man and his hoe®, chickens are not cackling all the time. But if you enter an egg laying house or poultry barn, the noise is deafening. They don’t make such continuous noise in a natural setting, so something is dreadfully wrong when they are packed in together.

Places Chickens Love to Roam

Today is the type of day chickens dream about. The weather is nice, and there are plenty of good things to eat around the pond. On days like this, they wander far. It’s not unusual to find a hen, hidden in thick grass, a long distance from any of the other chickens.

The first set of poles is done. The ones stripped last week are quite dark. Once the poles are up, they will make for a unique fence.

First Trillium

While clearing one of the forest trails, I saw two trilliums in bloom, the first of the year. It won’t be long before the forest floor is wall to wall trillium blossoms. It’s a luxury being able to leave the house and be in the forest in a few steps. In twenty years, this forest may be gone and this trail a parking lot of a mall. It seems impossible now, but every mall and strip mall within a hundred miles of here was at one time a thick forest where trilliums bloomed each April.

The next time you drive to a mall, park and step onto the asphalt, stop and imagine what used to be there: giant cedars, vine maples, alders, lush mosses, a doe with her fawn, fresh air. Could it possibly be that again?

Maybe when this lot is paved over, there will be plaque mentioning how in the past, a man raised chickens here, chickens who got to see trilliums blooming in the forest.

If you’ve never seen trilliums blooming in a forest, don’t wait. Venture into the woods. Find some trilliums and enjoy how peacefully they bob their graceful white or purple heads above their green skirts. Someday the forests may be gone and you will have missed your chance.

Where Chickens Like to Live

Mothers making baby food – a pernicious trend?

Sometimes I wonder if some corporate executives ever stop to think what their words sound like. I was reading an article in the New York Times yesterday, As Parents Make Their Own Baby Food, Industry Tries to Adapt, by Stephanie Strom. Evidently sales of prepared baby food are falling because more parents are making their own baby food. Doesn’t that sound like a good thing? Instead of relying on the factory kitchens of large corporations, parents are making fresh food for their babies. Great! Right?

But it’s not a good thing if you are a corporation relying on sales of baby food for your profits. According to Jeff Boutelle, chief executive of Beech-Nut Nutrition (owned by Hero Group of Switzerland), mothers making their own baby food at home is a pernicious trend! This is the quote in the article:

“Underlying our problem, there was a silent, pernicious trend going on that no one was really paying much attention to,” he [Jeff Boutelle] said — mothers making their own food at home.

“Today, moms are 50 times more busy and don’t have the cooking skills that women did when we introduced baby food 80 years ago,” Mr. Boutelle said. “But the category is so bad that they’re going to the grocery and spending an afternoon boiling and cooking and filling jars and sealing them because they don’t like what’s on the shelf.”

Well, hopefully this pernicious trend of parents making their babies’ food will continue, and as far as the women not having the cooking skills of moms from yesteryear, if that is the case, the solution is teaching those skills, not reducing them by offering even more processed foods.

pernicious – having a harmful effect, esp. in a gradual or subtle way: the pernicious influences of the mass media.

Blocking Traffic or Early-Onset Alzheimer’s?

I have yet to figure this one out. Cognac has taken to sitting in the doorway of the chicken yard. She likes to roost on the doorsill, facing the inside of the chicken yard, causing a chicken traffic jams. Is she craving attention? Or does she forget why she is going back into the chicken yard and is trying to recall the reason? Is this what early-onset Alzheimer’s looks like in chickens?

She and her sister, Hennessy, are three years old and still laying dark eggs. These are the eggs they laid yesterday. Quite a few of the chickens at a man and a hoe® are their offspring.

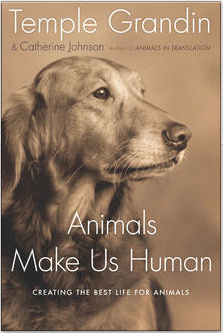

In a typical egg laying operation, three year old hens (156 weeks) don’t exist. Most hens are done with after either 70 weeks or between 100 and 130 weeks. Those that make it to 100-130 weeks, have gone through a forced molt, a rather gruesome practice. Dr. Temple Grandin and Catherine Johnson write in Animals Make Us Human: Creating the Best Life for Animals:

Forced molting shortens the time the chickens spend replacing their feathers and gets them back into full production faster. To force-molt an egg-layer flock, farmers shorten the hens’ daylight hours to six to eight and starve them for ten to fourteen days. That makes the birds mold and shortens the molting period by eight weeks, but it is very cruel. The hens’ mortality rate doubles, they become aggressive, and they develop stereotyped pecking and pacing. They are probably suffering severe frustration of the SEEKING system and overactivation of RAGE.

The next time you buy eggs, take a moment to ask yourself if the hens which laid those eggs suffered a forced molt. If you don’t know, consider asking the poultry farm which produced your eggs if they force molt their hens. It’s your food. You have every right to know how it was made, after all, you are going to be putting it in your mouth.

- The Disposal of Spent Laying Hens – The Animal Welfare Foundation of Canada

- Commercial Egg Production and Processing – Purdue University

- Forced Molting – Wikipedia

- Forced Molt: Starving Hens For Profit – NW Edible

- HSI Lauds India Ban of Starvation Force Molting of Laying Hens – Humane Society International:India

- How to Read Egg Carton Labels – The Humane Society of the USA