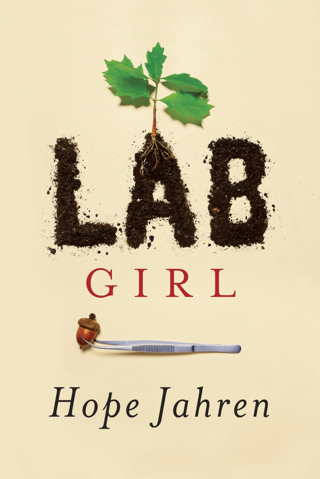

I haven’t laughed so hard in a long time. Lab Girl is an autobiographical book by scientist Hope Jahren. She intermingles chapters about growing up and the challenges she faced in her career as a woman scientist, among chapters about plants, especially trees, that she has been studying for decades.

I haven’t laughed so hard in a long time. Lab Girl is an autobiographical book by scientist Hope Jahren. She intermingles chapters about growing up and the challenges she faced in her career as a woman scientist, among chapters about plants, especially trees, that she has been studying for decades.

I could relate to her description of her life growing up in a Scandinavian family. My background isn’t Scandinavian, but Mennonite culture shares similarities:

… silent togetherness is what Scandinavian families do naturally, and it may be what they do best.

Throughout the book are many observations about plants and trees, such as:

There are about as many leaves on one tree as there are hairs on your head. It’s really impressive.

and:

In order to prepare for their long winter journey, trees undergo a process known as “hardening.” First the permeability of the cell walls increases drastically, allowing pure water to flow out while concentrating the sugars, proteins, and acids left behind. These chemicals act as a potent antifreeze, such that the cell can now dip well below freezing and the fluid inside of it will still persist in a syrupy liquid form.

and:

It is the gradual shortening of the days, sensed as a steady decrease in light during each twenty-four-hour cycle, that triggers hardening. Unlike the overall character of winter, which may be mild one year and punishing the next, the pattern of how light changes through the autumn is exactly the same every year.

In between the chapters about roots and leaves, wood and knots, and flowers and fruits, she describes hilarious scenes like the time when one of her students decided to become a veterinarian in order to work with endangered animals, only to discover during an internship at the Miami zoo, that what zookeepers mostly do is routine animal hygiene, such as applying anti-inflammatory cream to monkey genitalia. It is Hope Jahren’s description of what that student had to do that had me on the floor, laughing in stitches.

The genius of her writing is that laughing opens the mind to learn, so when she describes how scientists discovered how trees communicate with each other over long distances, you remember the details.

She ends on a somber note about what we humans are doing to this planet:

Our world is falling apart quietly. Human civilization has reduced the plant, a four-hundred-million-year-old life form, into three things: food, medicine, and wood. In our relentless and ever-intensifying obsession with obtaining a higher volume, potency, and variety of these three things, we have devastated plant ecology to an extent that millions of years of natural disaster could not. Roads have grown like a manic fungus, and the endless miles of ditches that bracket these roads serve as hasty graves for perhaps millions of plant species extinguished in the name of progress. Planet Earth is nearly a Dr. Seuss book made real: every year since 1990 we have created more than eight billion new stumps. If we continue to fell healthy trees at this rate, less than six hundred years from now, every tree on the planet will have been reduced to a stump. My job is about making sure there will be some evidence that someone cared about the great tragedy that unfolded during our age.

We’ve all witnessed this. When I used to live in Seattle, I was a member of a hiking group. Every Sunday we gathered at a Denny’s on Mercer Street, had breakfast, and headed out into the mountains for a hike in the mountains. When we decided to go for a hike in the central or northern Cascades, a highlight was getting north of Everett. Just on the other side of the Snohomish River, you drove out of urbanity and into the forest. For a long stretch, on both sides of the freeway, towering firs beckoned you into the wilderness beyond.

In 2003 or so, I was devasted when one summer, we drove north, and on the west side of the freeway, the entire forest was mowed down. It is now 250 acres of paved parking, casino, hotel, box stores, and an outlet mall.